It’s quite easy for someone to enjoy film. Loving film is completely different. For those who see film enjoy them, yet only those who can read film truly love it and understand it as an art form. Hitchcock is probably the most well known director of all time. There is no absolute answer to what his crowning achievement is. A lot of critics prefer “Vertigo”. Taste varies from one film lover to the other. “North by Northwest”, “Notorious”, “Vertigo”, “Rear Window”, “The Birds”, “Shadow of a Doubt”, “Strangers on a Train”, “Rebecca”, “Suspicion”, “The 39 Steps” and “Psycho” are among his most loved. The truth is there is no such thing as one ultimate Hitchcock masterpiece, there are only favorites.

Every month or so, I tend to invite a close group of film professors, directors, editors, writers, and critics to my living room. We watch some of the greatest films together. The screenings always end with insightful conversations, debates and arguments. We cite critics like Roger Ebert, Pauline Kael, and Robin Wood to back up our claims but to what end? Cinephiles tend to be stubborn. It’s almost impossible to convince a real lover of film that this scene is better than that one or this director is more talented than the other, etc. At the end, all you get is a fueled argument that does not lead to any absolute conclusion. I learn a great deal about film at these gatherings. During the past few weeks we watched about fifteen Hitchcock films. We studied them shot for shot. After the last screening, I asked the room full of film lovers about their favorite Alfred Hitchcock film. All of the above as well as others were mentioned and the room went into complete utter silence. “How strange” said a senior professor. “For the first time we’re not arguing with one another”.

Such is the case with the greatest of artists. We all have our favorite Shakespeare play or Mozart symphony. There is no need to argue for them and against the rest, for all are truly great in their own right. Hitchcock fans don’t dispute one another; they simply nod in respect, for unlike lesser directors, he doesn’t have one obvious masterpiece but an entire body of them. My favorite Hitchcock is “Psycho”. However, I respect almost all of his films equally. To me watching “Psycho” is like listening to the best of Mozart or Beethoven. The way Hitchcock uses the conventions of films is beyond words. Don’t expect to feel that way from one viewing. The first time I saw “Psycho”, all I could see was a horror film with a great twist and wonderful performances. I watched it a second time in my first film class, another time in a different film class, and several times after that. Today, I lost count of how many times I watched it, and how many times I studied it (there’s a difference). As my understanding of film grew, so did my appreciation for the brilliance of Hitchcock’s groundbreaking 1960 masterpiece, “Psycho”.

I mentioned at the beginning that it is one thing to see a film and another to have the ability to read a film. Many fans of film claim to love the movies but fail to understand this concept. One learns how to read film by learning about the medium and everything that constitutes the making of a great picture. It is only through the understanding of film that true love for movies sparks giving the ability to read films. Take for example, Mozart’s darkest opera “Don Giovanni”. It is one thing to listen to it and admire the flow of his music; it is another thing to listen to it knowing that his father died shortly before it was conducted. With that knowledge in combination with the music itself one can feel Mozart’s sorrow and grief. Through knowledge we open our hearts and emotions to the greatest works of literature, music, and film.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of “Psycho”. Therefore as a tribute, I’ll do my best to read this masterpiece and document it in written form. Hitchcock once said that he enjoys “playing the audience like a piano”. With “Psycho” he manipulates our expectations. Today about everyone knows what happens during the shower scene and the truth about Norman’s mother. (If you don’t stop reading and do yourself a favor, watch the film) Still, even with that knowledge, the joy is in observing how Hitchcock manipulates his audience. He often used diversions to misguide the audience. A simple example of this is placing a growling dog to block the stairway in “Strangers on a Train”. The dog is meant to distract the audience from guessing the surprise in the next scene. Hitchcock worked that way; he didn’t only control his cast and crew but his audience as well. With “Psycho”, the entire first act is a diversion.

I can only imagine the horror of sitting in a movie palace when “Psycho” first premiered. The audience must have felt excited having booked their tickets in advance and making it on time for the film. Hitchcock didn’t allow late entrances. So there they are sitting, excited about the next Hitchcock masterpiece. The lights dim, the black and white “A Paramount Release” logo appears on the big screen, and then total darkness as the logo fades to solid black. Suddenly, the first wave of Bernard Herrmann’s score fills the theater, the most horrifying music in film history. The black screen is split into stripes of grey during the opening credits. The audience doesn’t know it yet but this split bares significance.

There’s a dark side to every human being. We’re not 100% good. Occasionally we slip into that dark side. If you’re lucky and smart you can save yourself from letting the darkness overcome you. Here lies the true horror of “Psycho”, the dark side of the psyche. Our main character is Marion. She’s a young everyday working woman. Unfortunately she acts foolishly and tries to steal a lot of money from one of her customers. However, before meeting her fate –getting stabbed while cleaning off her sins in a shower – the guilt she feels deep down in her stomach pulls her out of the dark and back to normality. The film takes a turn there as we’re introduced to a much worse case of – the split. Norman plunged into madness and embraced darkness long before Hitchcock introduces us to him. Hitchcock’s choice to film in black and white was clearly not only to give the film a darker theme or to escape the sharp scissors of the censors; the black and white fits the theme of the picture.

“I enjoy playing the audience like a piano.”_Alfred Hitchcock

The movie starts one afternoon, as the camera moves from the outside of a city through a window into an apartment. Note Hitchcock opens the film by panning through a large city (Phoenix Arizona), the choice is random, so is the date (Friday, December the Eleventh), as well as the time (Two Forty-Three P.M.) The camera then moves through a random window of one of the many buildings. Hitchcock strikes the first note on his piano. Through these random choices, Hitchcock subliminally tells the audience that this tale can happen to anyone, anywhere, at any time.

We get our first glimpse of the main character. Or is he? She’s a blond, which is a Hitchcock trademark, so she must be – at that moment so it seems. Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is wearing a white bra and cuddles with her secret lover. Hitchcock picked that white bra at the beginning to signify her innocence. Later on, after she steals the money, we see Marion in a black bra, signifying her darker side. At one point, her boyfriend, Sam Loomis (John Gavin) suddenly releases the arms so passionately holding on to the love of his life. This is the exchange of words that follows:

Sam: “I’m tired of sweating for people who aren’t there. I sweat to pay off my father’s debts, and he’s in his grave. I sweat to pay my ex-wife alimony, and she’s living on the other side of the world somewhere.”

Marion: “I pay, too. They also pay who meet in hotel rooms.”

Sam: “A couple of years and my debts will be paid off. If she remarries, the alimony stops.”

Marion: “I haven’t even been married once yet.”

Sam: “Yah, but when you do, you’ll swing.”

Marion: “Oh, Sam, let’s get married.”

Sam: “Yeah. And live with me in a storeroom behind a hardware store in Fairvale? We’ll have lots of laughs. I’ll tell you what. When I send my ex-wife her alimony, you can lick the stamps.”

Marion: “I’ll lick the stamps”

Through this dialogue we learn that they can’t get married for financial reason, but what Hitchcock is doing on a deeper level is somewhat justifying the heroine’s future actions. That way we don’t despise Marion for committing theft. Instead, we understand her troubles and feel for her. In other words, she has a reason for stealing the money. Another example of Hitchcock trying to justify her theft is evident in the next scene. We meet Mr. Cassidy, a man who sprays his money everywhere to “buy happiness”. We don’t regard Marion as a villain because the man she steals from is portrayed as a very rich disgusting beast who doesn’t know how to hold his tongue. He speaks his mind with no manners whatsoever flirting with Marion and embarrassing the boss (“where’s that bottle you said was in your desk?”). After the theft, no real harm is done, at least not enough to make Marion a villain. We simply see her dark side. Again, this is expressed visually when we see her staring at the open envelope wearing her black bra. The $40,000 in the envelope serves as the ‘MacGuffin’ of the film. The term ‘MacGuffin’ refers to an object that bares much importance to the characters but to the audience it’s only a vehicle to drive the plot to the next level. A ‘MacGuffin’ is dropped once it serves its purpose.

Between the first justification scene and the second one, there’s the famous shot of Hitchcock’s trademark cameo. He stands outside a sidewalk, when the camera leaves the frame following the entrance of our main character. This is simply a visual signature. Hitchcock was well known at the time, not just by the name stamped on the previous “North by Northwest” posters but by introducing the episodes of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” on television. The same crew that worked for the TV series worked with him to deliver his small budget project to the big screen. Anyway, his appearance is a visual signature and a reminder that things will turn ugly. It’s Hitchcock.

“Psycho” revolutionized cinema, both technically and in terms of content. A perfect film to study various uses of editing, the rhythm in “Psycho” can be observed in how Hitchcock handles the passage of time very efficiently. When Marion leaves the room, we realize that it’s still that same day. She goes to work, collects some money she’s supposed to put into the bank and goes back home. All that happens in one particular afternoon, and the time frame doesn’t change. Janet Leigh’s performance shines in the next scenes. We return to her room. There is no need for dialogue; we know what she’s thinking when her desperate eyes land on the envelope. Like the greatest of silent performers, Leigh expresses more through facial reactions than words. Few actresses can pull this off, she does. After she decides to run away with the money, the editing becomes more and more interesting.

Hitchcock uses a medium shot of the main character, Marion Crane, as she drives away from her hometown. The shot shows her face, part of the steering wheel, and the background, which includes the sky. The shot then changes from that particular medium shot to what is regarded as an eye-line matching shot, in which we as the audience see the highway through her eyes. This is the second time Hitchcock uses this shot (the first being her staring at the envelope repeatedly). The minute she steps into her car, the narration starts.

The narration serves as the voice in her head. At first, we hear what she suspects Sam will react like upon seeing her with the money. Hitchcock just slipped us into her shoes. He doesn’t only establish her as the main character, he confirms it. We see what she sees (eye-line matching shots), we feel what she feels (the urge to steal the open envelope full of cash), and now Hitchcock makes her share her thoughts with us. She bites her finger in a traffic light stop. After that we get the eye-line matching shot. People cross the street in a hurry. Their hurry is nothing compared to that of Marion, especially when her eyes meet those of her employer’s. We get a close up shot of her smiling at him. Her boss smiles back, then stops realizing she’s supposed to be sick at home or on her way to a bank. He looks back at her, only this time more suspiciously. Enter Herrmann’s score, the plot thickens.

At first Marion’s expression suggests fear. Then we get a couple of night shots with bright lights striking our eyes. Her facial expression is more relaxed now. The following morning, Hitchcock is generous enough to provide a beautiful deep focus shot. On the lower left corner of the screen the trunk of Marion’s car, behind it, a police officer’s car, on the right, the long endless highway and in the background empty hills. It’s a feast to the eye. The officer walks up to the car, we see Marion sleeping in her. A few knocks on the window later, she wakes up in a hurry. We see the same look in her eyes as when she saw her employer crossing the street. The next shot serves as both an eye-line matching shot and a close-up of the expressionless police officer. By now, like Marion, the viewer suspects she’s been caught. It turns out, he’s just checking if something’s wrong. Marion acts “like something is wrong” and so he asks for her driver’s license. As soon as he leaves and Marion drives off, the horrifying orchestra starts again.

We get a few rear-view mirror shots as she tries to lose the officer till he takes a turn and leaves her alone. Shortly after, Marion trades her car for another one. Both the viewer and Marion see that the police officer is back. He studies her from across the street like a suspicious stalker. Hitchcock’s fear of cops tightens the tension. More importantly, we are introduced to the third suspicious character, the car salesman, the first being the boss, and the second, the police officer. Marion is doing a terrible job of getting away with crime. Afterall, she’s no professional, just an everyday woman.

We rarely get to see scenes like that in thrillers; scenes that serve little purpose to the story but are there to put us on the edge of our seats driving the plot forwards. These short scenes are a rarity and a treasure. Hitchcock is simply playing piano with the audiences’ nerves. By now the viewer is in the midst of a getaway thriller. Keep in mind that all these tiny scenes are a distraction of the bigger picture. After, the high-pressured car salesman scenes, we move forward to more medium shots of the steering wheel, Marion, and the fading city in the background. This time, she bites on her lower lip as we hear the narration or an imagination of a conversation between the suspicious police officer and the doubtful salesman. Hitchcock knew that people generally do most of their thinking when they’re alone. Like before we sleep or when we drive alone in an empty highway. These scenes are very psychological in that for the briefest of moments the viewer becomes Marion.

Gradually, her facial expression changes from scared to confident. Scared when imagining the discovery of her crime in a narrated conversation between her boss and her co-worker (played by the excellent Patricia Hitchcock) and confident when we hear Mr. Cassidy cursing her. A creepy smirk curves her lips. Marion still wants to go through it.

The viewer notices that the bright sky turn darker and darker, and eventually it starts to rain. Marion pulls over to sleep it off at some motel, the Bates motel. The first half of the movie takes place in two days, a continuous moment-to-moment spectrum of events. The pace and movement through time changes afterwards and is well defined through editing.

Marion pulls up in the rain to the Bates motel and sees the moving silhouette of an old woman in the upstairs window of the mansion. Hitchcock often features familiar landmarks in his films. In “Psycho”, he creates one with the Bates mansion. The gothic mansion stands on top of a haunting hill like “it’s hiding from the world”. The Bates mansion is now one of the most famous film sets around the world, the presence of the mansion is so powerful, it’s like a main character. Anyway, Marion honks the horn of her new car. Seconds later, Norman appears on the stairs in front of the haunting mansion up the hill. He then runs towards the motel to serve his only customer of the night. What follows are some of the most humorous Hitchcock moments of all time. (*Humorous only on repeated viewings of the film)

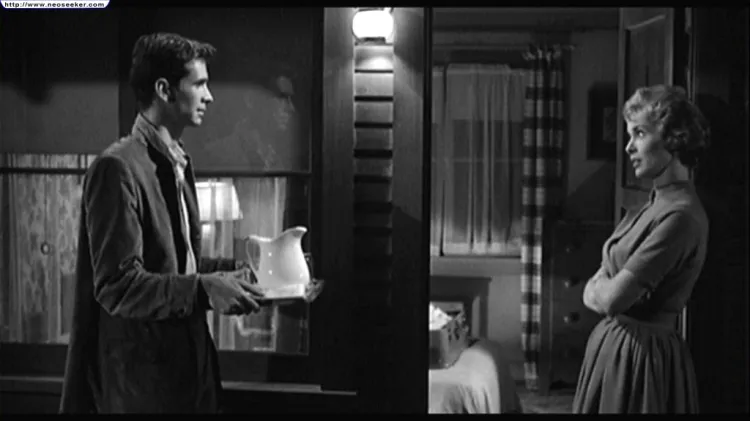

Norman Bates – cinema’s most famous villain. Anthony Perkins pulls it off right from the start. They check in and we are first introduced to Norman. Perkins plays the role in an oddly chilling loose and naturalistic manner. Marion signs as ‘Marie Samuels’. Again, the alias signature is pathetic as it’s proof of her not doing a good job of hiding her real identity. Marie is too close to her real name, Samuels is her boyfriend’s name. Norman asks her to write her home address as well. She looks at the newspaper that reads ‘Los Angeles Times’ and chooses that city rather than Arizona. “Los Angeles” she says. Meanwhile Norman chooses something else, a key to the room she’ll be spending the night in. Unlike the three suspicious men prior to that scene, Norman doesn’t suspect a thing. Why? – Because he’s hiding something himself. Norman picks room number one. “Cabin 1. It’s closer in case you want anything” Both character’s suspicious actions cancel each other out. A perfect scene as only the audience is aware of the humor in their interaction.

Consciously the first time viewer is not aware of it, but what Hitchcock is doing is something no filmmaker dared to pull off before. He’s slowly switching main characters through the only characteristic both Marion and Norman share. Hitchcock often referred to “Psycho” as pure film. The change of viewer’s attention and leading characters through the overlapping personality trait in a single scene is indeed an example of pure cinema. Of all my years as a film critic, I’ve never seen anything quite like this, except maybe in the scene that follows.

Norman shows Marion to her room. “Boy, it’s stuffy in here.”- A tongue-in-cheek remark. Norman goes on with a tour of the cabin. “Well, the mattress is soft and there’s hangers in the closet and stationery with Bates Motel printed on it in case you wanna make your friends back home feel envious. And the…” he switches the light of the bathroom on and struggles with the word. “Over there”. Marion helps him out: “The bathroom.” The awkward moment between them suggests that we should pay attention to any scene that’ll take place in the..over there.

Norman insists that they have dinner together. “nothing special, just sandwiches and milk. But I’d like it very much if you’d come up to the house” Another diversion by Hitchcock. Norman offers his hospitality. Contrary to what the viewer knows at the moment, Norman has a stuffed body up there. The last thing he’d want is for it to be discovered. The young man leaves, Marion wraps the money in newspaper. “NO I TELL YOU NO!”,an angry old woman shouts from the mansion. Marion stops her unpacking to eavesdrop.

Angry Old Woman: “I won’t have you bringing strange young girls in for supper! By candlelight, I suppose, in the cheap, erotic fashion of young men with cheap erotic minds!”

Norman: “Mother, please!”

We now know the angry old lady is his mother.

Mother: “And then what, after supper? Music? Whispers?”

Norman: “Mother, she’s just a stranger. She’s hungry and it’s raining out.”

Mother: “Mother, she’s just a stranger. As if men don’t desire strangers. As if….(shuddering) I refuse to speak of disgusting things, because they disgust me!”

What follows is a dim and haunting wide-shot of the house in complete obscurity with creepy tree branches on both sides and dark clouds lingering in the sky. Like a house on a haunted hill, the cinematography is simply breathtaking and needs to be seen to be believed. Only one light shines, the window of the room where the shadow of an old woman roamed earlier.

Mother: “You understand, boy? Go on. Go tell her she’ll not be appeasing her ugly appetite with my food or my son! Or do I have to tell her cause you don’t have the guts? Huh, boy? You have the guts, boy?”

A radio actress by the name of Virginia Gregg perfected that spine-chilling voice of mother. In fact, it is done so well, there’s no way the audience would suspect she’s just Norman fulfilling his disorder. Not only that but the fact that mother offers to go tell the visitor herself only personifies her leaving the viewer with no hints to guess the twisted reality.

A few seconds later, my all time favorite two-shot arises. Holding a tray with the milk and sandwich, Norman stands to the left in front of a window. Marion is on the right in front of the door. Both are standing outside in front of the cabin. “I’ve caused you some trouble”, Marion says implying that she heard their conversation. To which he replies: “No…mother…my mother…what is the phrase? She isn’t quite herself today.” Freeze the frame at that precise moment and observe the richness of the moment. Visually this shot speaks volumes of Hitchcock’s famous wit. In crisp clarity we see the reflection of Norman’s face on the outside window. Indeed “she isn’t quite herself today”, the answer is there visually. This may either be a coincidence or a stroke of genius. I like to think it’s the latter, for the blinds are half drawn providing the possibility of the reflection. It had to be intentional.

They move to the parlor because “eating in an office is just too officious”. Marion’s eyes study the furniture of the room. Stuffed birds make up most of the furniture. Hitchcock often used birds as symbols. Most famously in “The Birds” where at the beginning of the picture we witness birds trapped in their cages. By the end of the film it’s the other way around with humans trapped in a house and the birds outside. The purpose of stuffed birds in “Psycho” has been interpreted several times. Norman explains that stuffing birds is his hobby; we later learn that he stuffed his own mother. One of the birds is an owl waving her wings symbolizing the furious side of his split personality (or his mother side); the calm crow is his calmer side (Norman side), or maybe they’re just there to disturb the viewer and place them in an uncomfortable surrounding.

After learning more about Norman’s taxidermy hobby, the conversation takes us deeper into his personality. Taxidermy is supposed to “pass the time not fill it” I can imagine the work, stuffing birds, and his own mother over and over using expensive chemicals. Poor Norman. One of the most disturbing lines follows expressing the oddness of this disturbed character: “Well, a boy’s best friend is his mother.” Moments later, Norman asks Marion where she’s heading. “I didn’t mean to pry”, he utters apologetically. Another humorous line, for Norman does pry in the scene that follows, not verbally though; he does it physically through a peephole.

During the course of this scene, the viewer is exposed to Psycho’s finest moment, a priceless exchange of dialogue. Through their connection we slowly remove our feet from Marion’s shoes and step into Norman’s shoes. The focus now is on Norman and his mother. After, Norman expressing the courses of his daily life with no friends and him putting up with his mother, Marion suggests he send her to a madhouse. A medium shot of Norman changes to a close up, not through a cut but by him moving forward to face the lens. He snaps at her. “We all go a little mad sometimes.”

At the end of the scene we learn that Marion changes her mind and decides to return the money the next morning. In other words, the getaway plot is no longer. The scene ends. Hitchcock just brought an end to his story; in the next scene he brings an end to his protagonist.

Norman takes a peak through the peephole and watches Marion undress. He then walks out of his office, up the stairs to the mansion. Once inside, he takes a step up the stairs and suddenly changes his mind and goes to the kitchen. As the audience, we know that Mrs. Bates is upstairs. It’s a simple scene the purpose of which is to distract the viewer from outguessing the master.

Meanwhile Marion calculates how much cash she’ll have to return out of her own pockets. ($700) After tearing the note to pieces she looks around and can’t find a bin and so she flushes it down the toilette. This was the first time the flushing of a toilette was seen on screen. The audience must have felt shocked at the sight. Yet it’s only a warm up to the major shock that follows. Hitchcock once said that the toilet shot is a “vital component to the plot”. My guess is it foreshadows the shower scene. After the brutal murder, we get a close-up of Marion’s blood flushing down the bathtub hole.

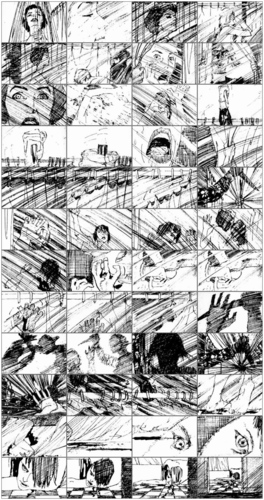

In probably the most famous, and well edited scene in all of cinema, also known as the shower scene, Hitchcock uses editing and sound as cinematic manipulation to create a carefully thought out horrific murder scene. Perfection is the result. In less than one minute, we witness a combination of 78 shots, in relation to the sound of a knife slashing against skin. We never actually see the knife enter the woman’s flesh, yet we’re convince we do through the sight of stabbing (hand motion), sound effects, the musical score (horrible animalistic screeching), and of course the careful editing. Celluloid cuts replace flesh cuts. When Hitchcock told Francois Truffaut that “Psycho” belongs to filmmakers, he wasn’t joking.

By exposing the audience to forty-five seconds of nonstop violence without actually showing any, Hitchcock leaves it up to our imagination. (Truffaut) Imagination has no limits which is why the scene is timeless and just as shocking half a century later. The shock is not only the sudden bombardment of cuts but the fact that he killed off his leading lady. We looked through her eyes, listened to her thoughts and witnessed her actions only to see her naked body slashed to an ugly death. With more than an hour to go, anything is possible. The viewer waits for the sound of Hitchcock’s next note on his piano.

Norman hurries in to clean up his “mother’s” mess. So not only do we witness the death of the leading lady, we watch Norman wipe the blood off the walls, the floor, the bathtub, and the sink after washing his bloody hands. After that, he wraps Marion’s dead body in the torn curtain. This mirrors the scene of Marion wrapping the newspaper around the $39,300 in cash. He then gathers her stuff puts it in the trunk of her car, along with the wrapped body and the wrapped “MacGuffin”.

The car slowly sinks into the darkness of the swamp. For a moment it stops. Here’s Hitchcock playing with his audience again. Even though we just witnessed our hero chopped and wrapped like a piece of meat, we somehow want the car to fully sink. It does. Fade to black.

Fade into the inside of a hardware store, Sam’s working place. One of the customers studies a can of poison “Let’s say see what they say about this one. They tell you what its ingredients are and how it’s guaranteed to exterminate every insect in the world, but they do not tell you whether or not it’s painless. And I say, insect or man, death should always be painless.” The viewer agrees. Afterall, the customer is always right. Enter Lila, Marion’s sister.

She’s worried and asks about the whereabouts of her sister. Sam is clueless. He tells his eavesdropping co-worker to go have his lunch. The co-worker leaves. Yet, the scene remains a three-shot with the entrance of a private investigator, Arbogast. All three ask questions, and eventually they’re all up to date. They realize that they’re all on the same side. Arbogast wants to find the missing money, Lila wants her sister, and Sam wants his girlfriend back. A new story unfolds.

As the story takes a different turn, so does the editing. The first half of the picture was edited to look like the events took place within two days. After, watching the story of the first half end, George Tomasini, the editor of the movie, speeds up the pace. In the scene that follows, Arbogast starts checking different hotels for any information on a missing Marion. The scene is a montage of a sequence of shots showing Arbogast in different hotels, which suggests the passage of time. Finally, Arbogast reaches the Bates motel.

Arbogast investigates right away. He makes the purpose of his visit clear and shows Norman a picture of Marion. Naturally, Norman is scared and tries to end their conversation as soon as humanly possible. “Well, no one’s stopped here for a couple of weeks.” Arbogast insists he take a look at the picture before “committing” himself. This is acting at its best. At first, Norman is relaxed offering his candy. Gradually as the pressure build up, Perkins’s performance intensifies. Arbogast catches a lie when Norman mentions a couple visiting “last week” and asks to take a look at the register. Perkins chews faster and harder on the candy (the candy was his idea). Norman takes another look at the picture and admits she was here but he didn’t recognize the picture at first because her hair was all wet. The showering of questions heightens the pressure and Perkins drives his performance into iconic status. We get it all complete with facial tics and stuttering words.

Being the great private detective that he is, Arbogast gets a more complete story by cornering Norman with questions. Moments later he spots the shadowy old woman in the upstairs mansion window. More of Norman’s lies are fished out and Arbogast takes another direction. He pressures Norman with the “let’s assume” method. To which, Norman mistakenly slips the words “Let’s put it this way. She may have fooled me but she didn’t fool my mother.” Now, Arbogast wants to meet the mother. To Norman that’s crossing the line, and so he asks him to leave.

A phone call later, the private-eye returns to the motel to fulfill his satisfaction. The sequence leading up to his murder mirrors that of Marion since both enter Norman’s patrol prior to their deaths. We also get the stuffed birds shots, only for some reason Hitchcock reverses them with the crow shot first and the owl afterwards. Nevertheless, the viewer is put in the same uncomfortable mood.

Arbogast goes up to the mansion, and step by step climbs the stairway. Hitchcock manages to pull off another shocking scene with a sudden jump-out-of-your seat appearance of mother stabbing the detective once he reaches the top. Blood splatters on his face, and we follow the fall with the camera fixed on Arbogast’s face. The same use of screeching noise is set by Herrmann. Once he lands, Mrs. Bates continues the stabbing, the detective screams in horror and the scene fades to black.

The Arbogast scene is the second and last onscreen kill. Today, Hitchcock is often credited with creating the slasher sub-genre. Unfortunately, this triggered a chain of terrible motion pictures with the exception of the original “Halloween”. Most of the slasher pictures of the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s and 00’s overdo it with frequent kills every other scene instead of building up the murder scenes with character development. Therefore, we end up with a bunch of characters we don’t much care for getting chopped to pieces. In “Psycho” it was never about the violence, it was always about the tension leading up to the violence.

Fade in, Sam and Lila sit worried in a smoky room “Sam he said an hour or less”. Sam: “Yeah, It’s been three.” As I said before the pace is much faster in the second half. Hitchcock directs this half like it’s a sequel requiring different editing methods. Likewise, time passes faster at Norman’s place. A medium shot of Norman standing in front of the clear black swamp. He’s already done cleaning the mess. Sam arrives and looks for “Arbogast”. He calls his name a few times with no luck. The medium shot becomes a close up, again not through a cut but by Sam walking up to the lens. He curves his hands around his mouth and gives it his all. The call for Arbogast echoes into the next and same shot of Norman in front of the swamp. We move closer to him. As his head turn to the right facing the camera, the camera pans to the left towards him. A very well executed shot is the result as we end with a close up on a chilling expression on Norman’s shadowy face. He’s looking at his motel.

A transition directs us to a deep shot of the storeroom. Lila is sitting at the center all the way in a lighted room in the back. The store itself is dark. She hears a car approaching stands up and runs through the dark store. We end up with a silhouette of her head in a close up. Without moving the camera, and with careful lighting, a simple scene becomes a memorable one. The movement is inside the frame as Lila breaks the depth of field of the shot. Previously Hitchcock created a close-up out of a medium shot, this time the task is difficult and much more impressive as he turns a deep focus shot into a close-up, without any cuts.

In a two-shot, the dark figures of Sam and Lila decide to see the deputy sheriff, Al Chambers. A transition leads to the deputy walking down the stairs. The camera slightly pans to the left and the camera is fixed on a four-shot (Sam, Lila, Mrs. Chambers, and Mr. Chamber). As Sam updates the sheriff with the story, we switch to a three-shot. Only this time they aren’t standing next to each other. The side of Al Chambers face is in the foreground and his wife, on the left, is in the background. When Sam mentions Norman’s mother the facial expression of Mrs. Chambers transforms to a look of panic and wonder. This shot is used to show the emotional reaction between the sheriff and his wife. After that we switch to a three-shot of Sam in the foreground, Lila in the middle-ground, and Mrs. Chambers in the background. Finally after constant switching from the two-shot to the three shot and gradually to one-shots, we end up with a low-angle shot of the sheriff and the spine-chilling line: “Well, if the woman up there is Mrs. Bates, who’s that woman buried out in Green Lawn Cemetery?” Hitchcock is involving the audience, moving us closer, building to more intimacy between the viewer and the characters. I like to call it the 4,3,2,1 scene.

The last line makes one question the existence of mother. Hitchcock is misguiding the audience. I bet a lot of the viewers were predicting a ghost story. The haunted mansion would fit that storyline, or maybe mother and Norman killed someone and made it look like mother died. The audience is in the dark.

Norman delicately walks up the stairway. He walks to mother’s room, and the camera slowly pans up closer to the door and eventually the long shot ends with an overhead view of Norman carrying his mother to the fruit cellar. This beautifully photographed shot meant to hide the face of Norman’s mother is an example of how Hitchcock uses cinematography to guide our eyes in whichever direction he pleases supporting the story.

Next, Sam and Lila decide to search every inch of the motel. To do so, they split up. Sam is to distract and keep Norman occupied while Lila goes up the mansion to get to the old woman. Two things happening at once builds the tension as the relation between both incidents eventually merge into the famous Norman in his wig scene.

Inside the office, Sam shoots accusations at Norman. He’s not as smooth as Arbogast which leads to trouble. They say an animal is most dangerous when cornered. The second time Norman is put in that situation, he breaks loose by striking Sam’s head with a souvenir. Meanwhile Lila after touring the house looks through a window and sees Norman running towards her from the Bates Motel. Space is all that was needed to keep us on the edge of our seats.

Moments later, Lila is hiding in the cellar room. She sees mother facing the wall in her rocking chair. A tap in the back later, the truth surfaces- mother is a corpse. Lila screams and hits a hanging light-bulb. Shadows dance. Enter Norman smiling like a creep with a kitchen knife high up in the air. More importantly the screeching noise makes another visit; the two previous times the audience listened to that horrible noise they witnessed murder scenes. Subconsciously the audience thinks it’ll happen again, only Sam comes to the rescue. The wig falls off Norman’s head.

The final scene is the famous psychiatry explanation. Like Roger Ebert, this scene always bothered me, for like the opening narration in “Dark City”, the full explanation underestimates the intelligence of the viewer. In his Great Movie essay, Roger provides a perfect cut: “If I were bold enough to reedit Hitchcock’s film, I would include only the doctor’s first explanation of Norman’s dual personality: ‘Norman Bates no longer exists. He only half existed to begin with. And now, the other half has taken over, probably for all time.’ Then I would cut out everything else the psychiatrist says, and cut to the shots of Norman wrapped in the blanket while his mother’s voice speaks (‘It’s sad when a mother has to speak the words that condemn her own son…’). Those edits, I submit, would have made ‘Psycho’ very nearly perfect.” (Ebert)

Even though the scene is not necessary, it’s not that much of a burden and doesn’t ruin the entire picture like the spoiler filled opening of “Dark City”. In the first half, we became so intimate with Marion, Hitchcock let us into her thoughts. In the final scene Norman, now the main character, shares his thoughts with the audience. Only his thoughts are those of his mother confirming the schizophrenic split personality disorder. “They’re probably watching me. Well, let them. Let them see what kind of a person I am. I’m not even gonna swat that fly. I hope they are watching. They’ll see. They’ll see and they’ll know, and they’ll say, ‘Why, she wouldn’t even harm a fly.’” A disturbing smile curves his face and a hint of mother’s skeleton appears as the transition escorts us the Marion’s car getting pulled out of the swamp. A perfect bloodcurdling last shot. The End.

Thanks for this! This post has been one of several of the great ways I’ve enjoyed Psycho’s fiftieth year — the others being more blog posts, rereading Wood’s book (Hitchcock’s Films) and of course watching the film proper: the 1960 and the … 1998 (which has its own virtues as expounded by Kim Moran here: http://bit.ly/cua1Sv).

My slant on the ending: it’s necessary. For a film that lies to us and has characters lie to each other (and, of course, to themselves), I think it’s both reassuring and unsettling to end it with (well, have the penultimate scene include) a pseudo-explanation.

If you listen carefully to what the doctor’s saying, most of it doesn’t make any sense. Or at least not enough sense.

Example: he says he got the whole story from the mother side of Norman’s personality. And that the mother is the one who committed the crimes. One tracking shot later, we’re in Norman’s cell and his mother-voice tells us “I couldn’t have them think I killed those girls” which is both true and false (she DID or was responsible; but she’s also been in the fruit cellar/bedroom for, what, ten years?) and also not what she would have told the doctor — it’s what he would have inferred from his interrogation of Norman.

Trying to very carefully parse what the doctor’s telling us and match it with our own “explanations” of the film and then realize the Norman, Lila, Sam, and probably Marion (before her pupils were dilated for all eternity) had radically different ways of understand the whole mad-man-stabs-hotel-patrons scenario.

Hitchcock is both offering us sense and nonsense. And what might on the surface feel like a copping out or a reductionism of the blandest sort, is, I think the final twist of a knife.

Unrelated but curiously apt example: Homer Simpson tries to be a better person through self-help books. He follows their advice, the book’s author visits the town, and now everyone is doing that particular personal-growth therapy/mode of living. Disaster ensues and the family Simpson is left in front of the tv, trying to figure out what’s wrong.

Marge says: “I guess this just proves self-improvement is best left to people in big cities.”

Lisa says: “No no no. Self-improvement can be achieved but not through a quick fix, it’s a long arduous process of personal and spiritual self-discovery.”

Homer: “That’s what I’ve been saying. We’re all fine the way we are.”

What seems like a comical and somewhat reasonable assessment (reasonable on the part of Lisa) is, it turns out, a dead end indicative of the misery and confusion of the entire episode.

When Hitchcock pulls out good old Simon Oakland to “explain” the film, he’s just adding to, not simplifying, the layers of density Psycho offers.

Whether it’s clunky or overlong or boring is another, separate issue. The effect of that scene is as powerful as, say, any of Arbogast’s moments on the screen: outside observers sucked into the vortex that is this film’s action and essentially impotent to come closer to the truth, just left to be swayed to hold some particular view that’s either misleading or incomplete.

LikeLike

Anthony, what an interesting comment.

I never looked beyond the surface of that last scene and may very well appreciate it more once I see it again. Still, the absence of that sequence would’ve triggered more debate and theories among us cinephiles. Don’t you think? Hitchcock’s film is among the world’s most debated and written on films ever made, so I don’t know if that would make much of a difference though..

Whenever I get to that scene, I don’t sigh or anything for 1 reason and 1 reason only. If it weren’t for it, we wouldn’t get that last spooky transition shot. I’m never ready for some new character to pop in and expect us to pay close attention to him or trust him..then again that does add to your interesting theory of what Norman or Norman’s mother really told him. How can we trust this guy?

I will disagree with you on one aspect- the remake. I hate it. The thing is, Hitchcock’s film was shocking and powerful at its time. It revolutionized cinema and changed everything. I can imagine films before and after “Psycho”. The difference of pre and post “Psycho” films is evident in film history. I don’t see the point in remaking a film that already did what it did. The 1998 remake came in with a shot-by-shot remake and added nothing new, because the first “Psycho” already produced its effect. Imagine if you will introducing ice-cream to the world. Once it melts in your mouth, you’re overcome by its amazing taste, the second scoop is not as effective because you arleady tasted it the first time. I don’t think I’m doing a good job translating my thoughts, but I’ll try again. “Psycho” (1998) came out in among in an already revolutionized era..it came out in a post-“Psycho” (1960) among other films that were already influenced by the original.

I think Roger put it perfectly in his review of the 1998 remake: “I was reminded of the child prodigy who was summoned to perform for a famous pianist. The child climbed onto the piano stool and played something by Chopin with great speed and accuracy. The great musician then patted the child on the head and said, “You can play the notes. Someday, you may be able to play the music.” (Ebert)

In addition to that, you have the casting. Vaughn is not nearly as good as Perkins. It’s his role, he played it to perfection. His career was never the same again because Norman stayed with him to the end. That’s how good he performed the role. Vaugh is still the funny guy from “Swingers”. The same goes for Leigh. Kim Morgan mentioned that before shooting the scenes of the remake she kept studying the expressions on Janet Leigh’s face, well..read the Roger comment above.

As I mentioned the black and white fit the theme. The dark cinematography was vital to that theme, the director may have shot it exactly as Hitchcock did but he failed to carry the spirit of the old one-the b&w photography.

LikeLike

Mmm. The snag is that a remark like this might also be made by a patronising passive-aggressive bully who feels challenged by a child’s genius. I’m not saying that the famous pianist is a patronising passive-aggressive bully challenged by a child’s genius, but merely that a remark like that is indistinguishable from one made by a patronising passive-aggressive bully challenged by a child’s genius.

But of course, regardless, the Hitchcock is the superior film if only on the grounds that it was there first. The only point of a remake is that the shock of a filmstar’s early demise in a film is lost if a modern viewer is unaware of said star’s fame.

LikeLike

I see your point but nonetheless it’s not about how you can imitate. It’s how you create. It’s easy for a painter to look at an old painting and recreate the same brush strokes but to paint your imagination is what’s all about.

LikeLike

Yeah. It’s definitely dicey territory.

I think of the psychiatrist as not really a new character, but a voice to a lot of the suspicions they audience may be having. He’s sort of like the stand-in for questions the film is asking, solidifying their ambiguity by his own clearly misled information, and also acts a lot like, say, Jerry the newspaper man in Citizen Kane — not so much a fully flushed character as a sounding board for the audience’s ambitions and readings about the film.

The remake is another beast for analysis. It’s in my experience a no-no to evaluate a film by comparing it to another, earlier work, saying “X fails because it doesn’t do what Y does.” But in the case of Psycho (1998) we’re left with a big question mark as to “how it compares” whether or not we’d like to assess it.

On its own terms, in its own little universe, Psycho (1998) isn’t a bad film. It’s beautifully shot, well-acted (again: not comparing Vince Vaughan to Anthony Perkins, but looking at Vince Vaughan as some guy Gus Van Sant hired to play a role and only that) and is captivating and engaging from from first to last frame.

Two things happen when you compare Van Sant’s remake to Hitchcock’s original. One is that you’re trying to balance the former’s failing with the latter’s flat-out excellence. Admission: Psycho (1960…) is my favourite film. I’ve seen it more times than I’ve seen certain members of my extended family. It makes me cry and changes how I see the world (a new way each time I watch it) and is technically and film-history-wise brilliant. It fails in utterly gigantic ways. Nobody could argue otherwise. With the exception of Nosferatu (Murnau and later Herzog), all remakes stink put in the shadow of the original film. So Van Sant’s Psycho pales in pretty appalling ways. Beginning with the b&w photography being replaced by attractive but not at all as affecting candy-coloured pallet.

Watching Van Sant’s remake, a second thing happens: each change (from the casting, which was a necessity, to the colourization and remolded sets, which were both choices) speaks volumes about WHY such a change was made — why is Norman Bates suddenly so much more guilty-seeming and aggressive in, say, the back-office (“we all go a little mad sometimes”) scene. Making a film, Herzog, I think, said, is the only way to criticize a previous film. (Maybe it wasn’t Herzog.)

Psycho-98 is postmodern criticism of a near-perfect film, and fails not just by that standard (what can really be added? that the secretary in the realtor’s office is so much more chattier and snarky doesn’t add to my understanding of that 1960 mighty and unsettling scene at all) but all the standards a critic could dream up.

Still. In some ways. It’s not a bad film. Comparing it to the original, you and Ebert are bang-on, it’s apparent that “there’s no music, only notes” — comparing it to other 1998 films and it’s clear that it’s a strong but not nearly as persuasive and shattering filmic experience as anything that year offered (good example: Dark City) — comparing it to the original in some sort of “cinematic commentary & criticism” is illuminating but not of the intensity of insight and overbearing light that, say, the bathroom in Van Sant’s literally shone into cabin number one (they must have used up like, 90 90-watt bulbs to make it that bright). It speaks a little, but not volume.

(Example of that: look how long Norman, in the Gus Van Sant remake, lingers over which key to give Marion while she’s responding that she’s “from Los Angeles” — see Zizek for an interpretation of that moment — how it suggests Norman sees Marion as some kind of loose city-woman; the lingering being an emphasis that was just a subtle touch in the original … and ultimately, I prefer the subtle touch.)

It fails for me, too, but I think it fails in peculiar ways.

And to round this off, quick anecdote: I agree. Vaughn is so clunky in his version. I first saw the film on television, just changing onto the channel as I saw Norman storm the cellar, half-cackling. Thinking of that awe-filled look of triumph Perkins had in 1960 made me giggle and think: “boy, did they ever drop the ball on that.”

Perkins gives, as a professor of mine once insisted, a performance unlike anything else in cinematic history. Given that Psycho was near-40 years before Psycho-1998, it’s not surprising that, as you say, the revolutionary aspects were already imbedded in film culture. All Van Sant can do that’s worthwhile is make his film, and have it point to the original, saying “go watch this.”

LikeLike

Anthony, you’re absolutely right. The prospect of remaking “Psycho” is as disgusting as getting a bad hair cut. The solution is to shave it all off, which is more or less what Gus Van Sant did. He eliminated the idea of ever remaking this masterpiece with his 1998 remake. I think it may be the only remake ever to be exactly like the original technically and in terms of content. (Expept maybe the masturbation scene but I think Hitchcock suggested it but couldn’t fully express it due to the limitations of his time in terms of restrictions)

By doing that, Sant had every critic question the purpose of making the film in the first place. “so no one else would have to” was his answer, and boy is the answer pitch-perfect. I’d rather eat rotten strawberries with fresh cream than rotten strawberries with no cream (Sorry for the constant food-comparisons. That’s what happens when you argue with me when I’m hungry hehe). Gus Van Sant proved himself to be an excellent director with his other films, so in a sense we know, the director is not an idiot trying to make a profit.

The fact that he did direct it and exactly so, makes room for healthy argument. Afterall, I’m sure if he didn’t someone else would. Hollywood is remaking “The Birds”!!! Can you believe it? I can, because it’s hollywood. Sometimes remakes are so horrible they can in a very subtle way ruin the love for the original, but that didn’t happen in this case. So in a weird indirect way, I’m both thankful and grateful for the remake even though I do not like it at all. It’s better to have a Gus Van Sant remake than a Rob Zombie reimagining.

LikeLike

That’s great! Yeah Rob Zombie should not be doing so much reimagining. I have an old beta machine he can play with if we have to keep him busy.

And yeah: I can’t think of any remake as Psycho-98 that is so much a Xerox.

I feel like Van Sant might have just loved the film and wanted to study it, recreate it, not unlike Scottie trying to remake Judy as Madeline — and we all know how that turned out.

I mean: if you gave me a million dollars (or several million) and were all “go nuts” I’d probably, had I already done some more personal projects, be like: time to indulge my Dreyer-fetish or whatever. (Can you imagine doing this with, say, Ordet? I’m like getting sick in ways that go beyond thinking of rotten strawberries.) 🙂

The Birds is a beautiful and perverse film. And Hollywood will do two criminal things to it: (1) is corruptly over-edit it with cross-cuts and rapid-fire the-birds-flying-everywhere kind of shots/cuts — what’s so perfect about the original is the way Hitchcock and his team make the editing’s pace frantic but not out of control and chaotic. Imagine all the muddled fight-scenes we see in, like, your average Hollywood fare (Clash of the Titans, say) and see it transposed to the material of The Birds. Blegh! Also (2) will be the total conventionality of the story — none of the disconcerting Freudian overtones, no Lacanian Real, no ambiguity over why the birds are attacking (at least none without a strong dose of Hollywood backstory). No good news at this prospect. At least Naomi Watts might be in it?

And at least when a director “reimagines” a masterpiece, it’s usually someone like David Lynch doing a Sunset Blvd-Vertigo-Persona synthesis as meshed with his own vision of cinema. Usually Hollywood remakes things that sold amazingly well.

But the problem (man, is this ever getting Long!) is like fifty years from now: 2060 when Psycho = 100 years old. Hollywood will probably “retool” it as a 3-D extra-sensory experience where real water falls from the theatre’s ceiling during the shower scene and like you can text in your opinion of how the movie should end (“Who the killer?”) and have that go up on the screen, by popular vote.

ALSO: the whole masturbation thing may have ruined Psycho (1960), at least for that one scene. I mentioned this in Kim’s blog’s comment-section, but the thing is: if Norman ‘climaxes’ before he kills Marion, you have to wonder why exactly he’d kill her — out of frustration? Would it be the mother-side of him punishing Norman for ‘enjoying’ his hotel guest, instead of for the desire of wanting her, threatening her role in his life. Huge questions. Good thing the censors probably would’ve cut it out anyway.

LikeLike

Anthony, that would be horrible. The whole 3-D interactive thing may bring an end to cinema, the way cinema brought an end to vaudeville. The only difference is, cinema improved upon vaudeville whereas interactive/3D filmmaking doesn’t.

As for masturbation scene, I think it would’ve been better if he tried but couldn’t climax. It would’ve spoken volumes about his sick split psychological state.

Your description of what “The Birds” remake will look like sounds very likely. I can imagine it being in 3-D too, with birds flying at the audience. (Yuck)

Anthony, you clearly are very knowledgeable when it comes to film. You fit the decription of my first few paragraphs. I hope to have more such discussion with a fellow cinephile who has what it takes to read films. 🙂

LikeLike

Having seen most of his movies, I would opt my preference for Rear Window, Vertigo and Psycho. What I remember most in Psycho is the beginning of the suspense, as the heroine drives away with the stolen cash–the score already makes us begin to salivate (if you can use that term for one’s own heart thumping) for the horror to follow. Psycho was one of those movies which you want to interrupt midway, so unbearable does the fear become. Double Indemnity and Stalag 17, not to speak of Halloween, generated similar reactions.

Your dedication is awesome. I will continue as an “enjoyer”.

LikeLike

I love “Rear Window”, and “Vertigo” too. “North by Northwest” is another popular choice, but in my opinion is fun whereas the former are “heavy” films with layers of psychological themes. “Shadow of a Doubt” was Hitchcock’s favorite, and like “Double Indemnity”, “Stalag 17”, and “Psycho” is makes us salivate 🙂

LikeLike

I’ve enjoyed reading your blog’s past entires (I just discovered it this week) and also look forward to more back-and-forth in the comments.

Cheers.

LikeLike

What great opening paragraphs, Wael! As for the rest of the post, I think I may have to paraphrase Roger’s tweet about my 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea review: I don’t think I’ve ever seen Psycho until I read this blog.

Anthony Perkins is amazing in this film. It’s criminal that he wasn’t even nominated for an Oscar.

Funny story: this was the first Alfred Hitchcock film that I saw, and as such, I thought it would be “scarier” than it was. Of course, now that I’m much older and wiser, I should be able to appreciate it more, and this shot-by-shot analysis certainly wets my appetite for another viewing.

LikeLike

Now, I want to read your “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” piece 🙂 (Link please).

I know what you mean about the “Psycho” being scary part. The thing is, “Psycho” is scary in a very deep psychological level. It’s not about the shocks and scares as much as it makes you wonder. There are real “psychos” out there, I hope to never meet one. Also the concept of Marion suddenly meeting her death so suddenly, it’s almost as if Hitchcock is telling us that death is right around the corner. At any time, during the day, it can jump right at you.

“Psycho” is more scary after you see it. It’s suspenseful during the ride but the true horror comes the more you think about it. Also, I doubt I’ll ever check into a motel alone, at a rainy night, in the middle of nowhere…ever.

LikeLike

Here’s the link for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: http://dreamsoflit.blogspot.com/2010/06/siff-week-three-stephin-merritt-and.html

Your comment about checking into a motel alone mirrors my reaction to Halloween, in that I always check the back seat of the car before I get in front.

LikeLike

Your post takes me back to when, in 1995, I was just a 12-year boy who had heard about Alfred Hitchcock and “Psycho” a lot and never had seen it. I had already read Robert Bloch’s book four years before and then watched two unnecessary but not-so-insulting sequels from TV(You know, Anthony Perkins was still good in these movies). Sadly, at that time, most of Hitchcock movies were not officially introduced to our VHS market, and only Hitchcock movie I had seen at that time was “North By Northwest”, my personal favorite along with “Vertigo”.

But the change finally came. Although it was not complete, but many of Hitchcock movies began to be released in video shops. I still remember the order: “Torn Curtain”(one of his few mistakes) , “Topaz”, “Frenzy”, “Vertigo”, “The Man Who Knew Too Much”, “The Rope”, “Rear Window”, “Marnie”, “Psycho”, “The Birds”, and “Saboteur”. Then it stopped there, damn it! I had to wait for more than 5 years for the era of DVD when almost every Hitchcock movies were released on DVD or pirate DVD here. “The Trouble with Harry”(Not great, but I usually watch it every fall), “Notorious”, “Shadow of A Doubt”, “The Lady Vanished”, “Rebecca”, “The Wrong Man”, “Suspicion”, “Foreign Correspondent”….

The detailed description by you transported me to the first watching of “Psycho” in 1995(As I said you before several times, I watched it after “The Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult) Even without still cuts, your writing is evocative enough for me to remember what I saw from TV in the living room during peaceful afternoon right after the final exam(I watched movies instead of opening bottles of champaign for celebrating it). Although I clearly knew what was going to happen to Marion, Hitchcock played me like a piano like any other audiences in last 50 years. In the book, Marion is a minor character introduced in the second chapter and then dispatched quickly at the end of the next chapter, but Hitchcock deftly fools the audience. With Bernard Herrmann’s main theme repeated again and again, we think the movie is about the plight of a young girl who happens to do the wrong thing. I did several tests with my friends, and even the one who knows about that infamous shower scene.

In case of that shower sequence… I have to confess that I once counted the number of the stabbing with shot-by-shot analysis. It’s around 14 times, but I’m not sure now. Anyway, that does not matter, and what implied and imagined from the sequence is really important. It’s not so bloody and looks very tame compared to the standard at present, but, like “The Exorcist”, it has the timeless terror that cannot be easily imitated. And it enhances the gloomy themes of the story itself. We’re in our personal trap and maybe we’ll never get out of it, regardless of how much we scratch and craw…. Sometimes we get mad, or the fate makes a cruel joke to us. The movie is ultimately pessimistic, but with skills and sly sense of humor, Hitchcock made one of his great films that still impresses many movie lovers.

I don’t intensely hate Gus Van Sant’s remake; I have a sort of cold admiration. He proved that the magic of the movies exist between frames, like the magic of the books between lines(or words). I wonder whether b/w would have made the movie a little better. Van Sant took the job of the bad guy, and now there will be no more remake of “Psycho”. At least, he did few things Hitchcock himself wanted but could not do, like opening sequence.

Meanwhile, Brian DePalma’s “Dressed to Kill” is an enjoyable rip-off “Psycho”(I even wrote about these two movies at English writing class). As the “The Master of the Macbre”, DePalma went more violent, but he also knew the power of our imagination. Although Elevator sequence is far more bloody than the shower sequence, the blood splattered on the wall is more terrifying than slashing itself. DePalma had amused us with many homages to “Psycho” and clever twists in this movie; he even “copied” that unnecessary explanation scene. Why? I don’t know, but it’s more amusing than original one.

P.S.

1. The more I look into the movie, I found Bernard Herrmann’s music is no less crucial in many scenes than famous sequences. For example, when Marion gets tempted by the money on her bed, ascending-descending violin chords with agitated viola play effectively reflected the state of her mind(Do it or Don’t do it?).

Interestingly, “Psycho” and “Taxi Driver” have the musical connection between them thanks to Herrmann. Ominous three-note “Madhouse” motif appears when Norman turns hostile due to Marion’s suggestion. It signifies the hopelessly deranged state of Norman and makes a gut-chilling coda at the finale. 15 years later, Herrmann used it again for another madness of a dangerous character named Travis Bickle. Again, he closed the story with “Madnouse” motif.

Hitchcock was not so confident when he completed the movie. He even considered to cut his movie down to an hour television show. However, Herrmann suggested him; “Why don’t you go away for Christmas holidays, and when you come back we’ll record the score and see what you think.” And the rest is, as we all know, the history.

2. How did people think about “Psycho” at that time? I got some glimpse from TV series “Mad Men”

http://www.lippsisters.com/2010/06/04/mad-men-at-the-movies-long-weekend/

LikeLike

What a wonderful comment. It deserves its own blog post. 🙂

Yes, “Dressed to Kill” was a very good homage to “Psycho”. The scenes you picked out are proof of that. I never actually read the book but from what you tell me, it was all Hitchcock. I often get into arguments with people over “Who should be credited with killing the main character off mid-way through the film?” I always said it must have been Hitchcock, but then they would point out the fact that it was based on Robert Bloch’s book and since he wrote it originally, the credit should be given to him. However, now that you’ve mentioned the fact that Marion is a minor character who only gets two pages of page-time (I think I just made up a word), you just provided me with a counter-argument. So thank you my friend. 😀 It was indeed Hitchcock afterall. Do you think I should check the book out? I hear they get more into the backstory of Norman, which is present in the sequels.

Herrmann is the Beethoven of film composers. That’s what I always thought anyway. His scores are not only there to inject the viewers with emotions but speaks of the situation in a scene and the character’s feelings at given moments. As you mentioned this is evident in “Taxi Driver” with the split score, the soft and the “doomed” heavy one.

Thanks again,

Wael Khairy

LikeLike

The book is a nice thriller on its own. I recommend you to read it, especially if you want to know what kind of books our naughty boy Norman has in his bedroom. The first chapter begins with Norman reading one of his books while spending another day of his cosy daily life with his equally naughty mother. Like the mother, like the son….

If they try remake again and try to be faithful to the original Norman Bates, I will recommend them Philip Seymour Hoffman as the lead. That’s why I was surprised by Anthony Perkins at the first viewing – ‘He looks better than me!”

LikeLike

I was told the original Norman is an overweight grumpy man and Hitchcock changed that. They did refer to the naughty magazines in the remake. When Julianne Moore searches the house she finds some mags in his room.

But come on! Even though Seymore Hoffman be great as Norman. The film is best left alone. 🙂

LikeLike

What a trailer–almost as good as the film itself ! It brought back the whole film seen five tears ago for the first and last time.

LikeLike

Yes, even his trailer was original! 🙂

LikeLike

You might be interested in animator Eddie Fitzgerald’s quick post comparing the original Psycho to the remake:

http://uncleeddiestheorycorner.blogspot.com/2010/10/about-psycho.html

LikeLike

Just a quickie – is there any way of finding out where some of the critical shots were taken? For example the crossroads in Phoenix where Marion and her boss see each other, the place on the highway where the cop wakes her up, the garage where she trades her car, etc? Could be fun to plonk them on google maps.

LikeLike

I found his: http://www.movie-locations.com/movies/p/Psycho_1960.html

LikeLike

Thanks!

(Sorry about late response – only just discovered unread email buried in ‘received’ folders, asking for subs-confirmation to your blog. Oops.)

LikeLike

I cherished as much as you will obtain carried out proper here. The cartoon is tasteful, your authored material stylish. nevertheless, you command get got an impatience over that you would like be turning in the following. ill unquestionably come further until now once more since exactly the same nearly a lot ceaselessly inside of case you defend this hike.

LikeLike

There are a few other things that bear commenting on. There are recurring references to romance/sexuality: The Rape of the Sabines painting that hides the hole in the wall, the shadow of the cupid statue as Arbogast starts up the steps, the “Eros” record in Norman’s bedroom, the way Norman steps toward Marion in the scene where he is bringing the sandwiches, then awkwardly takes a step back as if afraid of getting physically close the woman his “mother” just verbally slammed.

LikeLike

Just sharing this post here for other film enthusiasts. Shot by shot of Last Chance Harvey firstfra.me/1fj0w01

LikeLike

This is marvelous and yes, you are so right in imagining the feelings we had the first time PSYCHO opened. To this day, I cannot figure out what OUR mother, an otherwise decent, protective, caring mother, could have been thinking to bring my sister and me to see PSYCHO when we were just kids. The whole movie had me biting my nails and fidgeting and when Norman began his murderous shenanigans, esp. the shower scene, I literally thought I was having a heart attack. And yes, it is true that after seeing that, my mother had an almost-impossible time getting Diane and I into the shower. I have watched this masterpiece many, many times since but I have never forgotten that first plunge into the deep, dark waters of Alfred Hitchcock’s genius.

LikeLike

Actually the entire film narrative is given birth by the first act.

LikeLike

I have a question: upon arriving at Bates Motel Norman is about to grab the key to cabin number three untill he hears her say she is from Los Angles. You can see in the movie that hesitation as his hand hovers in front of three before he quickly grabs key one and explains that it’s better then the other rooms because it’s closer.This was my first time watching the movie and I did really enjoy it but that scene kind of bugged me.why was Los Angles a trigger word?

LikeLike

Well spotted, never noticed that. However I think it’s just a coincidence, I’ve always felt that he decided to give her cabin 1 so that he can look through the spy hole, but he does hesitate as she says ‘Los Angeles’ so who knows? I’ve never seen it commented on and I’ve read up a lot on the film.

LikeLike

Good piece; one thing I spotted which you haven’t mentioned is that there is a classic piece of foregrounding in the dialogue between Marino Crane and the traffic policeman, who says “You slept here all night? There are plenty of motels in this area..I mean, just to be safe…”

Overall though I do in general dislike the somewhat toadying attitude to Hitchcock (and other film directors) that critics tend to have. Many of the strengths of his films lie at the hands of his composers, writers and cinematographers, although his influence is of course key. Often not enough credit is given to Robert Bloch, or Joseph Stefano, and without Herrmann’s music it wouldn’t be half as memorable (and don’t forget Hitchcock originally didn’t want any music in the shower scene – watch that scene with and without the music and you’ll see what poor judgement that was). Some his shots and set ups simply don’t work (the way Arbogast falls down stairs is ridiculous) as can be seen by some of the worst model shots and backdrops in film history that occur throughout many of his films (with the backdrop of the ship in Marnie being pretty much unbeatable). He is also a pretty poor critic of his own work, if you watch his interviews, some of what he says actually makes little sense (in Psycho for instance, he talks about rejecting Bass’ idea of having the camera focus on the bannister etc, claiming that it was not a scene for tension, when it is obvious that the scene is tense and suspenseful, particuarly when the door to Mother’s room comes ajar). Could make many other comments but enough!

LikeLike